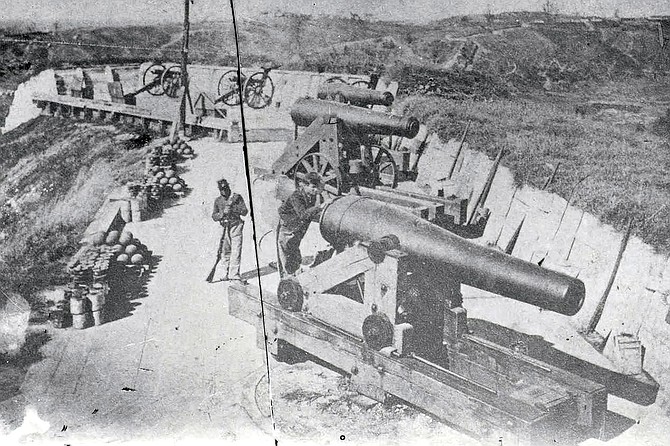

The 5th U.S. Heavy Artillery, an African American regiment in the Union army, was stationed for garrison duty in Vicksburg, Miss., during the Civil War. Photo courtesy National Park Services

“Wilson Brown, born in Natchez, was a Navy Landsman and was one of the eight African Americans who was awarded the Navy and Marine Medal of––”

“I need a n-gger on line 2. A n-igger on line 2 please,” a male voice interrupted Natchez Monument Committee Member Deborah Fountain, a Black woman.

Fountain tried to continue with her presentation on the history of the U.S. Colored Troops, but she was interrupted again with more racial epithets from the virtual attendees of a public town hall meeting on Nov. 10, 2021. Everyone could hear the insults, with many attendees gasping in shock and disgust from the repulsive interruption.

“N-gger boy,” a different male voice speaks up.

“N-gger,” a female voice added. “N-gger,” she repeats.

It was silent for a moment before Fountain made a fourth attempt to finish her presentation. There was a slight catch in her voice, but she powered through despite the moment.

The program organizers manage to get the trolls booted for the rest of the night, but one can never underestimate the overt racism that makes itself known during events that celebrate and uplift the Black and brown Mississippians of the past and present.

Grappling with Confederate History

The Natchez U.S. Colored Troops Monument Committee hosted the town hall meeting to get community input on a potential monument to honor and showcase the names of more than 3,000 African American men who served with the colored troops at Fort McPherson in Natchez during the Civil War and the Navy men who served and were born in Natchez.

The southwest Mississippi city of about 15,000, which gained its initial wealth and power from plantations worked by enslaved Black people, has long celebrated its Confederate heritage with dress-up pageantry. But in recent years, it has started publicly grappling with its history, including as the site of the second largest domestic major slave market in the Deep South at Forks of the Road. Now, organizers of the town hall believe it should celebrate local Black soldiers’ role in the downfall of the Confederacy and the liberation of enslaved Black southerners.

“On Jan. 1, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation. It declared all persons held as slaves, in the rebellious states, to be free,” History and Research Chairman Deborah Fountain told the audience. “And number two, it announced the acceptance of Black men into the Union Army and Navy, enabling the liberated to become liberators.”

By the end of the Civil War, around 180,000 Black men had served as soldiers in the U.S. Army and 20,000 Black men served in the Navy. On May 22, 1863, the U.S. War Department issued General Order 143, which created the United States Colored Troops.

The Union army took control of the Mississippi River following the fall of Vicksburg on July 4, 1863. During the occupation of Vicksburg, colored troops performed duties such as drill, police duty, picket-line duty outside the city, mandatory school attendance and service details around town, the National Park Service reports.

“Officers thought the United States Colored Troops required more supervision and detailed instruction than other troops. The USCT were also held to a much higher standard than their white counterparts and punished more frequently if they failed at their various tasks,” the site reads.

Punishment did not include whippings due to its ties to slavery, but depending on the offense, it could include execution. While in Vicksburg, the troops protected the city and changed some people’s minds about their capabilities. Though final troops withdrew from Vicksburg in 1877, many former troops remained there and were later buried in the Vicksburg National Cemetery.

‘Many Had Bravely Left Plantations’

On July 13, 1863, nine days after the Fall of Vicksburg, Union troops arrived in Natchez and General Ulysses S. Grant established union headquarters at Rosalie Mansion. Three weeks later, U.S. Colored Troops regiments began to be raised in Natchez.

“A large number of these Black men who enlisted were from Natchez, or many had bravely left plantations in the Natchez district and surrounding counties and fled to Natchez and enlisted,” Fountain said.

During the fall of 1863, soldiers began to work on the construction of a five-sided earthwork fortification named for Gen. James “Birdseye” McPherson and included the Marine hospital in the northwest corner. Soldiers received orders to demolish the slave pin at the Forks of the Road and use the wood for the construction of the fort and its barracks, she said.

More than 3,000 U.S Colored Troops served in six regiments at Fort McPherson. Those regiments included the 6th U.S. Colored Heavy Artillery, the 58th U.S. Colored Infantry, the 70th U.S. Colored Infantry, the 71st U.S. Colored Infantry, the 63rd U.S. Colored Infantry and the 64th U.S. Colored Infantry. The monument will honor these regiments.

Natchez’ population is 63% Black, and the committee is encouraging families to look through their family trees and visit the National Park Service’s website to search for ancestors who served in the military during the 1860s on the United States Colored Troops list. “It is believed that up to 90% of individuals of long-standing Black families in Natchez may be descendants of the Natchez colored troops, soldiers and sailors, but may not know it,” Fountain said.

‘Not Just a Statue’

Monument Design Chairman Lance Harris and his committee compiled ideas and thoughts for what they would like to see in the monument. Many of the members, he said, sent in examples from similar memorials throughout the country. Examples included the Alexandra, Va.,-based Contraband and Freedmen Cemetery Memorial as well as and The Ark of Return: A Slave Trade Memorial in New York City, which the committee shared with town-hall attendees.

“There was a lot of talk about this being a place of meaning and not just simply a statute and also being able to tell a story and provide narrative for the past and the present at the particular time during the Civil War,” Harris said.

The chairman said he and committee members discussed the use of different walkways, textiles and auditory elements they could implement that would leave people with an experience to remember.

Natchez residents will have the opportunity to give their thoughts on the monument project through surveys the committee gave out as residents signed into the meeting. Residents can decide if trees or plants will be included in the monument, what materials the monument should use and the site’s location.

“We’re going to take this information, we’re going to compile it, and we’re going to put it in a packet along with some other information to go out to design teams,” Harris elaborated.

Site Subcommittee Chairman Devin Heath created a list of 13 potential site locations that they eventually narrowed down to eight options based on criteria such as historical significance, access to residents and visitors, site visibility and security, and other factors.

“Would there be the potential for future encroachment for existing facilities or future development? Would there be potential with flooding? What is the road access and capacity?” Heath said about the committee’s concerns.

Heath said his site committee is working very closely with the design committee to best accommodate the ideas the community puts forth for the project. The eight sites that the site committee chose include Natchez Memorial Park; Forks of the Road; Cemetery Road overlooking the cemetery; corner of North Martin Luther King Jr. Street and Gayoso Street; Zion Chapel AME Church; North Martin Luther King Jr. Street and B streets; a plot of land behind Pig Out BBQ; and the Natchez Visitor Reception Center.

“Those are the sites we evaluated, (but) we haven’t made any final decisions. That’s why we wanted to have it be a part of this conversation today. As we progress through this meeting, we welcome any feedback that the community has,” Heath said.

Mayor Dan Gibson, the chairman of the finance committee, announced the project’s website where people can read about the monument and send donations. Soon, the project will have a bank account in Natchez with a direct link to the website for people across the country to contribute, he said.

The mayor said the contributions are tax-deductible through the nonprofit Community Alliance Fund. The mayor made the first pledge of $1,000 and is encouraging people to give as little or as much as they can.

“So many have given so much for our freedoms, and we have for many years been paying homage to these individuals,” Gibson said. “Numerous monuments dot the landscape of America from sea to shining sea, and yet these over 3,000 Americans have been, for the vast majority of 150 years and counting, overlooked. It’s time in Natchez that we correct that.”

Fundraising committee Chairman Robert Pernell announced that the committee had recently been approved for nonprofit-foundation status. Pernell said the committee hopes to receive funding from athletes who are from the Magnolia State.

“I know the mayor said give what you can, but we want to go after those who we know got some money,” he said, laughing.

Marketing and PR Subcommittee Chairman Roscoe Barnes III rounded out the presentation by stating that the time has come for this monument project to take fruition and the committee is doing all it can to get the word out.

“I want to encourage you if you’re on Facebook to follow our page. We encourage you to follow where we will be posting updates on a regular basis. We’re using other social-media platforms as well. When appropriate, we’re using LinkedIn, we’re using Twitter. We’re using Instagram. We’re using Tumblr,” Barnes said.

The marketing chair said the committee is also sending email updates about the project. He said the committee is very grateful for the local and area news coverage they’ve received so far.

‘City Park, B Street and MLK’

Lee Ford, a Black resident, was the first attendee to approach the microphone. Ford told the committee that he is a direct descendant of several of the colored troops and has served in the military himself. The 61-year-old declared that he was a proud Natchez native and supports the monument project because it is time for all the men of service to be recognized.

“It needs to go up, but it needs to go up in an environment where it needs to be. I saw several suggestions on the bluff, which is a great place, but I feel the most significant place would be City Park,” Ford offered.

Ford was speaking of Natchez Memorial Park, where several U.S. Army, Air Force, Navy and Marine Corps monuments are erected. But among the statues in the park stands a Confederate statue, placed there in 1890, that honors Confederate soldiers from Natchez-Adam County who died during the Civil War.

“There is nowhere in this country today that you could put up a Confederate statue. Point. Blank. Period. If it was wrong now, it was wrong then. I’m not saying to tear the statute down. I’m saying move that statue to a place of its nature,” he expressed.

In April, the Natchez Board of Aldermen heard a request to remove the statue from the park, but most of the board voted to delay the final decision on the monument’s fate.

Ford went on to say that the statue represents oppression, insurrection and servitude—a reminder of a time when Black people weren’t even allowed in the park unless they were working there.

“I want everybody to be happy. We need to be together. The only way we can be together is to start the foundation of doing everything right,” he said.

Tour guide Betty Hicks, a white resident, wants the committee to consider the accessibility of motor coaches in regard to site location. Joseph Smith, an online attendee, took interest in seeing the monument put in an area of town that would help expand tourism into areas that aren’t as tourist-heavy as others.

“I love the idea of having the site located near B Street and MLK, and I think the issue of parking is one that we overcome like we do with any other tourist spot where the motor coaches drop people off to visit the prospective site and the bus pulls off,” Smith said.

Though he liked the idea of the statue being put in Memorial Park, he’s concerned that if all the tourist attractions continue to be placed in the downtown area, then visitors aren’t afforded the chance to witness all the culture and heritage the entire city offers, he said.

Betty Sago, a Black resident, wants to make sure that the monument is just as accessible for residents as it will be for visitors.

“The walkers, the ones who want to park or if you got a transit bus, they can bring them wherever they need to go. We need to be inclusive and not just talk about motor coaches. We need to be inclusive with whatever site,” she said.

She also added that a good majority of residents don’t know anything about the Colored Troops, so she suggested efforts to educate the community about them first. “You most definitely want your community to be educated about what happened in their city,” Sago added.

For more information about the U.S. Colored Troops project, visit organizers’ website and follow their Facebook group. To donate to the project, click here. If you are a Natchez resident who wants to know if any of your ancestors were a Colored Troop, you can visit the National Park Service website.

This story originally appeared in the Mississippi Free Press. The Mississippi Free Press is a statewide nonprofit news outlet that provides most of its stories free to other media outlets to republish. Write shaye@mississippifreepress.org for information.

More like this story

- For Miss., an Angst-Filled Civil War Anniversary

- Natchez Trace Threatened by Budget Fight

- Confederate Statue at Raymond Courthouse May Move After Black Citizen Pleads Case to Supervisors

- Military Plans Would Put Women in Most Combat Jobs

- What Follows Confederate Statues? One Mississippi City's Fight

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.