Through the decades, Malaco Records has worked with top music artists such as Frederick Knight, “Bobby Blue” Bland and George Jackson. Photo courtesy Shorefire Media

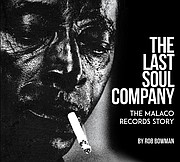

Rob Bowman's March 23, 2021, release, "The Last Soul Company: The Malaco Records Story," came to my doorstep in a pizza box-sized package that utterly bemused my poor postman, who is otherwise accustomed to dropping off the several deliveries I've received as part of my reviewing work with the Jackson Free Press. The reason for the bulky packaging was immediately apparent—the book itself is a coffee-table book, heavy, with a glossy black-and-white cover image of a Black man smoking the last few drags of a pale cigarette.

The inside of the manuscript is no different, with the academic writing punctuated by photographs, often stopping the text for pages at a time to include pictures taken at the Jackson recording company through its five decades of business, which the book commemorates. Stills of the artists that propelled Malaco's rise to fame stud its pages, but it features just as many "behind-the-scenes" looks at the company that is now the longest-standing independent record label in U.S. history.

A quick thumb-through of the well-researched tome makes it evident, then, that Malaco Records's success was synonymous with the success of its Black artists, who pioneered the stylings and sounds that helped the label stay afloat even during the rocky years when disco dominated the charts. Bowman does not ignore the contribution of Black artists to the last soul company's success—indeed, their contributions are unignorable in the larger story of late-20th century blues-infused music.

Bowman does, however, seem to water down the Black experience that made such soulful stylings possible. After all, Malaco Records got its start in Oxford, Miss., signing Black artists to perform during the same decade that left two people dead and 300 injured on the campus of the state's flagship university in the wake of the admission of James Meredith, the University of Mississippi's first Black student.

The focus instead is often on the white proprietors of the label, who were gifted at plucking artists from obscurity and helping them select songs and records that would elevate them to the top of their corners of the music world. Bowman makes it clear that this corner of the music world was often a specific one, as he points out that Malaco's only number-one records came on the gospel charts, a considerable distance from the more mainstream pop and rock offerings of the day.

Still, the company enjoyed unabated success, employing nearly 200 at its peak. Hard times eventually befell the Northside Drive edifice, as several of its premier performers eventually succumbed to poor health or the evolving music scene, which larger media conglomerates overtook by purchasing independent radio stations.

Bowman laments this transition, noting that when smaller radio stations from Houston to Gulfport stopped being able to select their own music—often the life-songs of their listeners, blues and soul and other undeniably Southern genres—the Mississippi record label suffered.

The overarching story of Malaco (at least in Bowman's estimation) is one of resilience, as the company has pivoted to promoting its music via streaming services and has rebuilt its physical location after an F-2 tornado devastated its original studio. And how could it be otherwise? The Black artists who put it on the map were and are well-acquainted with tenacity, with persisting in spite of seemingly overwhelming odds in the face of a larger mainstream culture that overlooks their talent at best and stifles them at worst.

Reading "The Last Soul Company: The Malaco Records Story" reminded me what a unique opportunity it is to build a life in Mississippi's capital city, which has so often fostered the talents of artists—musical, literary, visual—that the rest of the nation would have allowed to fade into insignificance.

After all, the rest of the nation so often thinks of Ross Barnett's dire warnings of "drinking from the cup of genocide" when confronted with forced integration when it thinks of Mississippi, but in Jackson, we know that while those aspects of our history are true and must be reckoned with (and are often not history at all, as they can unexpectedly rear their ugly heads and remind us that they still live with us in the present), so are the successes and talents of our citizens, who bravely sing a song of better times and a brighter future in the sharing of their gifts.

Purchase the book through malaco.com or at Lemuria Book Store.

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.