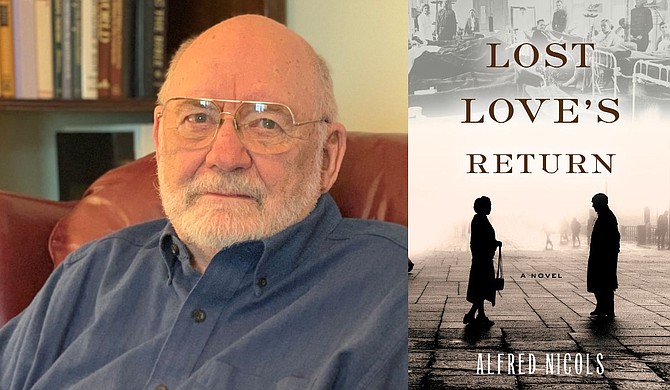

In Mississippi author Alfred Nicols’s “Lost Love’s Return,” the return is all the sweeter for the loss, as Nicols spins a tale of World War I sweethearts separated by illness, scheming lovers and the Atlantic Ocean. Photo courtesy Alfred Nicols

In Mississippi author Alfred Nicols’s “Lost Love’s Return,” the return is all the sweeter for the loss, as Nicols spins a tale of World War I sweethearts separated by illness, scheming lovers and the Atlantic Ocean. Peter Montgomery is a simple, down-home boy from a small town in southern Mississippi who meets London native Elizabeth Baker at Edmonton Hospital after his leg is filled with German shrapnel. The pair fall deeply in love, but when Peter is shipped back to America with no way to leave word of his whereabouts for Elizabeth, the two begin to chart very different courses for their lives.

These diverging paths are indelibly marked by their time in the Great War, and the novel probes these difficult questions of war without coming to any convenient (or preachy) conclusions. Peter agonizes about the fact that he, a boy who once cried on a squirrel hunt over the inhumanity of it all, killed countless men in the name of war, and Peter and Elizabeth both feel the burden of surviving the war when their loved ones did not. In this cycle of refusing easy answers, Nicols makes room to ask the axial question on which the novel cleverly pivots: What is a man’s duty?

When Peter returns home from the war, heartbroken over his perceived loss of Elizabeth, a young shopkeeper in his hometown sets her sights on Peter. Her wicked influence is the true unspooling of his relationship with Elizabeth, as she hides the letters marked “return to sender,” thereby depriving Peter of the knowledge that Elizabeth never knew that he tried to find her. The shopkeeper, however, does something far worse: She takes advantage of a drunk and sleeping Peter to have the necessary fodder for a believable lie of pregnancy. Had the same happened to Elizabeth, it certainly would have been decried as rape, since no consent was ever given (in fact, Peter protested).

Instead, Peter feels responsible, and the polite Southern culture of his Mississippi hometown feeds this sense of responsibility, with his parents telling him to do “the right thing,” despite the fact that he bore no responsibility for the act. Duty, then, becomes a construct that Peter dismantles throughout the novel. His duty to his country left him with mental and physical scars, and his duty to the mother of his child leads him into a loveless marriage that will eventually leave him penniless and alone, as the shopkeeper spends Peter’s working years spiriting away nearly every dollar he ever made.

The story rang true for me, since, like Peter, I’m a native of South Mississippi (his fictional hometown couldn’t have been far from my own, as it’s remarked that he lived an hour from Hattiesburg but nearly three hours from Jackson—those are the same geographical relationships I use to describe Wayne County to people who don’t know where it is). I’ve seen countless people decide to jump the broom when someone falls pregnant, even if there’s no love in sight. Duty harms men and women alike, the novel contends, keeping them from love and happiness and any real notion of who they actually are outside their ideas of “should do” and “ought to do.”

The novel’s conclusion is satisfying because, however belatedly, Peter is eventually able to answer the question of who he really is and what and who he really wants. It’s a privilege denied to many other Southern young people who feel the weight of the “right thing” when it doesn’t look or feel right to them in the context of their own lives and their own sense of being. Seeing Peter—at almost 50 years old—reclaim his life and provide his son an example of another way to live and another way to be a man was refreshing in the world of Southern literature.

Interested readers can purchase Nicols’s “Lost Love’s Return” on Amazon, at Target or from Barnes and Noble.

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.