District Attorney Jody Owens explained in an interview in his office on July 8 that Hinds County needs more resources to reduce the time detainees spend in Hinds County Detention Centers before going to trial. Photo by Kayode Crown

The last attorney who worked with Justin Mosley, 21, before he was found hanging in his Hinds County Detention Center cell in Raymond was Malcolm O. Harrison. Hinds County Circuit Judge Eleanor Faye Peterson appointed Harrison as Mosley’s defense attorney on Feb. 9, 2021, after the public defender withdrew, citing conflict of interest. That attorney, Michael Henry, said that a witness in the two-count alleged murder charge against Mosley was once his client.

When Mosley died in detention on Sunday, April 18, 2021, one month before his 22nd birthday on May 18, he had been in custody for 16 months. Harrison told the Jackson Free Press that Mosley did not indicate suicidal tendencies the various times he spoke with him. “I met with him three or four times during the time period that I represented him,” Harrison said in an Aug. 20 phone interview.

“Between my time with him and his unfortunate demise, I never saw—I’m not a medical doctor—but I never saw signs of hopelessness. I never saw signs of, you know, of suicide. And I didn’t see that. I was as surprised as anybody (by his death),” Harrison added.

“(His mother, Chalonda Mosley) was very involved in calling my office, and she had unique insight obviously into Justin Mosley. She told me on several occasions what his medical diagnosis was, what his issues were and how best to deal with it. Again, I just never saw any of that.”

Harrison declined to share what the reported medical diagnosis was.

The attorney provided an email address and a phone number for Chalonda Mosley, but she has not responded to emails or phone calls.

Mosley’s indictment for murder in July 2020 came after he had already spent more than six months in jail. By the time he died in April, the accused had spent 16 months in incarceration, and his trial had not even begun. Peterson had set it for Sept. 13, 2021, after appointing Harrison.

But the 16-month stay would not be the first time Mosley would spend extended time in jail without a trial. On May 22, 2019, court documents signed by Hinds County Circuit Court Senior Judge Tomie Green showed that Mosley, at that time, had been held for six months without trial. The charge was for assaulting Hinds County Deputy Sheriff Johnny Ransome at a basketball game at Raymond High School in November 2018. The court-appointed defense attorney filed a motion to dismiss the charges for due-process violation on April 11, 2019, because of the lack of trial since Mosley’s Nov. 16, 2018, arrest at age 19. Green reduced his bond to $5,000, and officials released him from jail on May 23, 2019.

The Mississippi constitution says trials should occur within 270 days of post-indictment arraignment. Uslegal.com said that the 270-day rule grants an accused person a statutory right to a speedy trial.

The indictment for assaulting an officer came a year after the alleged act, on Dec. 12, 2019, with Judge Peterson issuing an order for Mosley’s arrest six days later on Dec. 18, 2019. Court documents show that officials reduced the charge against Mosley to a misdemeanor in September 2020, sentenced him to six months in prison and released him on time served. But he remained in jail for the murders he allegedly committed on Jan. 26, 2020, after his arrest three days later. He allegedly killed Djuana Robinson and Michael Lawson at an apartment complex at 1101 Highway 467 in Edwards, Miss.

Court documents revealed Mosley’s alleged additional offenses in jail. On Oct. 9, 2020, in the Hinds County Detention Center in Raymond, Mosley allegedly “snatched Deputy Martravious Elkins’ less-lethal shotgun inside A Pod Unit-(1) in the facility.” On Jan 10, 2021, he allegedly “kicked the cell dirt windows of C pod unit 4 repeatedly until it shattered.” On Feb 11, 2021, Mosley allegedly sprayed pepper spray on detention officer Marcus Wilson. The investigator, Martravious Elkins, said Mosley refused to speak with him about spraying the officer.

Based on available records, Mosley was in jail from November 2018 to May 2019 and from January 2020 to April 2021, totaling two years without going to trial on any charge.

Hinds County Detention Numbers

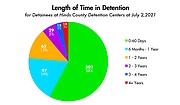

Fifty-eight people in Hinds County Detention Centers by July 2, 2021, had spent more than two years there, documents the Jackson Free Press obtained show. The facilities hold 521 detainees at that time. Renewed concerns about the length of time pre-trial detainees spend at the Hinds County Detention Center and the Work Center, both in Raymond, surfaced after county officials found Mosley hanging in his cell in April after being locked up for 16 months.

On July 6, another detainee, Johnny Woodrow Gann, 33, was also found hanging in his cell, the second this year. Hinds County Sheriff’s Office spokesman Tyree Jones said in a July 12 interview that Gann had been indicted for burglary and was a convicted felon in possession of a firearm. He had been in jail since March.

Hinds County District Attorney Jody Owens talked in a July 8 interview about the different innovations his office has tried since his election in 2019, but he added that the volume of crime in recent times is a significant issue in how long the accused stay in detention without a trial.

“Realistically, we know the intake of crime in 2019 and 2020, and still what we’re seeing in 2021, the current system is not yet equipped to handle the volume of crime we have with the few judges we have,” Owens said. He ran as a “decarceral” prosecutor, meaning he pledged to free more people accused of non-violent crimes on the way to reforming the county’s criminal-justice system, or help track them into alternative programs.

Decreasing the pre-trial backlog in the county detention centers was a campaign point for candidates for both sheriff and DA in the 2019 elections, including late Sheriff Lee Vance and Owens, saying they would lead on a holistic analysis of the Hinds system, including the judicial branch. Vance died on Aug. 4 after testing positive for COVID-19 following an outbreak of the virus in Hinds County jail. Marshand Crisler is acting sheriff.

Owens told the Jackson City Council on May 4 that his “smart justice” initiative has diverted 400% more people from the criminal-justice system than the previous year. “We gave more boys and girls who are non-violent offenders second chances,” he said. Back on Jan. 26, 2001, Owens said he had diverted 300 in a press briefing recapping his first year in office.

Need More Judges

The district attorney said in the July 8 interview that if the judges in the county work a full schedule, there will still be significant backlogs and that he has been reaching out to state officials to get more resources. The Legislature approved one-year funding for two attorneys to work with the Hinds County district attorney’s office.

“We need permanent positions, but certainly we don’t want to be ungrateful for any help because we certainly need all the help we can get. But in addition, we need at least one, if not two, judiciary seats, and we need another fully funded judgeship in Hinds County. That’s my position,” Owens explained.

“And when I say fully funded, I mean a full-time judge, a full-time court reporter, a full-time law clerk, a full-time court administrator, those four positions, full judgeship, and also, of course, court bailiffs,” the district attorney added.

Need More Judges, Or Not?

Mosley’s last attorney, Harrison, had extensive experience in the practice of law in Hinds County, including serving as the prosecuting attorney for 10 years (1999-2009) and as a circuit judge (2009-2011). He said adding judges is a solution to the accused not spending extended time in jail as pretrial detainees in the county.

“I just think we don’t have enough judges. We don’t have enough prosecutors to handle the caseload in Hinds County. Hinds County has a large number of violent criminal detainees, and you need more judges and more prosecutors, more assistant district attorneys, they handle all the cases,” Harrison said.

Mississippi State Public Defender André de Gruy said in a phone interview on July 12 that he had not seen any evidence of an increase in crime that would justify needing another judge, as Owens had stated. De Gruy emphasized that additional judges may not be the panacea if the process of gathering evidence to present the case is not more effective.

“I keep hearing that there’s this surge in crime, but I had not seen any evidence of actually an increase in crime in Hinds County, or even in the city of Jackson,” the public defender said. “What we know is that there’s an increase in homicides and aggravated assaults.”

“So if you get 2,000 cases, 40 extra homicides isn’t going to show up as an increase in crime. But, you know, we recognize that those cases are going to take time,” De Gruy added.

“If the backlog is on gathering evidence, whether it’s evidence from the Jackson Police Department on their investigation or it’s the medical examiner’s office, or it’s the investigation from the defense after everything’s turned over to them, you’re not going to speed up the case (by) just putting a new judge there. The cases are still not going to be ready.”

BOTEC: ‘Archaic Practices’

Concerns of delay in processing cases in Hinds has been a longstanding concern. The Mississippi Legislature, in 2014, and then-Attorney General Jim Hood commissioned a study of causes and solutions for Jackson crime. One of the BOTEC Analysis Corp. reports, released in November 2015, focused on prosecution and case-processing times.

“In particular, the stakeholders wanted to know what resources are required to move cases faster, and whether Hinds County has a sufficient supply of those resources,” the report stated.

BOTEC noted that “there was a perception that long case-processing times emboldened criminals by creating a sense of impunity.” The report said the priority should be to get the process right by better court-management practices before adding more staffing. “All available evidence indicates that professional case-flow management is more effective to improve performance than increased staffing, but it is not available in Hinds County,” BOTEC investigators found.

“The lack of support by professional court managers means that judges work harder while being slowed down by archaic practices,” BOTEC explained. “Good institutional management requires ensuring that a system is working as efficiently as possible before assuming that increased staffing is needed.”

District Attorney Owens told the press in January that his office is using an ineffective system to manage its workflow. “One of the challenges that we have is that we have antiquated software. It’s very difficult for us to keep the data the way we want it to be. We’d looked at getting upgraded systems and working with the board of supervisors on providing that,” he explained then.

The 2014 BOTEC report emphasized the importance of overhauling the county’s court system’s processes before any other step.

“Unless the Hinds County Circuit Court Clerk’s Office overhauls its docketing and data-collection practices, the effectiveness of any attempt to improve case-processing speed will remain unknown because outcomes cannot be measured,” the BOTEC report said.

“All open cases should be managed in a computer system that accurately identifies significant court events so that case status may be correctly assessed.”

“Priority should be given to improving quality of data reporting, with periodic audits and cross-checking to ensure that statistics are properly generated,” it added.

“When the court can reliably track case information, improvement efforts can begin.” It is unclear if the county has taken those steps.

Hinds County Circuit Clerk Zack Wallace told the Jackson Free Press in a phone interview on Aug. 31 that the county has complied with the electronic filing of cases since 2014 based on Mississippi Supreme Court’s order.

“We are doing all the docketing for circuit and county court,” he said. “I have attorneys emailing me documents; attorneys can actually file their own dockets on MEC—that is Mississippi Electronic Court.”

“So there’s nothing slowing down with the circuit clerk’s office, and filers are not slowing down at all,” he added. “Even if the judges have to file an order or something, they can email it to me, I have access at home, or I go to the office to make sure it goes into the file, and once it’s uploaded to the file, all the attorneys that are registered in that particular case number, they receive a copy of that document.” He said that the other items are up to the judges’ court administrators.

Green: Double The Judges

Hinds County Circuit Court Senior Judge Green also says the various issues affecting the extended stay of inmates in Hinds County court for decades include an inadequate number of judges.

“Our number needs to double, even if they only double for a while, and then if the caseloads go down, certainly the Legislature can reduce it,” she told the Jackson Free Press on July 26. “But right now, there’s no question that we need more judges, courtrooms and staff.”

The current four circuit-court judges handle felony cases, with municipal or county courts dealing with misdemeanors. The Hinds County Circuit Court covers two judicial districts, which include 10 cities: Jackson Terry, Byram, Clinton, Pocahontas, Edwards, Bolton, Utica, Pocahontas and Raymond.

“The four judges have to take care of all the felony cases that come down by indictment. I have to do those cases in between the indictment and when they are arrested, hearing the motions. And I am supposed to be reviewing all the people in the jail to see if there are people there 90 days or more who haven’t been indicted,” Green said in the interview.

“But in the meantime, the DA is every month indicting more people, more charges,” she added. “Now we could have cases that are back four, five years old, just the volume of cases for four judges.”

Green said the judges’ job also includes civil cases with plaintiffs seeking a minimum of $200,000 in damages, serving as appellate judges for lower courts and tribunals, defendants already in jail, filing post-trial motions, and cases filed against the State of Mississippi.

“And with four judges, that becomes extremely difficult,” she added.

Having been a judge since 1999, as well as the first woman judge in Hinds County Circuit Court and a lawyer for 15 years before that, Green says there is a noticeable increase in the volume of cases at the Hinds County Circuit Court.

“I don’t think anyone has looked at Hinds County to see whether the volume of cases requires a larger number of judges at the circuit level,” she said.

“I’ve been here from the time that I was practicing law for about 15 years before I even took up the bench. But there were only four judges then, and it’s still only four circuit judges now.”

“But we just need more judges. I think the caseload justifies it, the work justifies it, the criminal docket justifies it, and we need twice what we have now,” she added.

“The volume of cases has increased, and early on when I was with the Legislature, we were trying to get the Legislature to underwrite additional judges for Hinds county, and they didn’t.”

Green was in the Mississippi House of Representatives from 1992 to 1998 before her election to the bench. Recalling the debates on increasing the number of judges for Hinds County and the objections to it, she said some say that the caseload does not justify it, and there was consideration for the financial implication on the county.

“At that time, I think one of the questions was not only is it that the State has to pay—the State only pays for the judges—it’s an unfunded mandate to your county,” the chief judge said.

Green said the county has to pay for support staff, including bailiffs, as well as provide offices and courtrooms, and everything else judges need to do their jobs, or reimburse the State for the expenses.

Waiting For Mental Evaluation

As part of Mosley’s prosecution for murder, the court, in its scheduling order for the case dated Oct. 20, 2020, said that the “Defendant shall within thirty (30) days from today’s date file their motion for mental evaluations pursuant to M.R.Cr.P. 12 (Mississippi Rules of Criminal Prosecution), motion for speedy trial and/or motion for bond.”

The order set the trial date for March 8, 2021, one month before Mosley was found hanging in detention. On Feb. 26, 2021, the judge moved the trial day to Sept. 13 after appointing Harrison as his defense attorney.

After the Oct. 20, 2020, court order, the next item in the docket was a Dec. 1, 2020, motion for bond by the defense. There was nothing about “mental evaluation.” After Harrison took over the case on Feb. 9, 2021, he filed a motion for discovery the next day. His request from the prosecution included “records, reports, results of any psychological/psychiatric tests of the defendant.” There is no indication that he got any information of that nature or if Mosley’s case ultimately warranted it.

However, many of the 521 detainees in Hinds County detention centers need mental evaluation for their cases to proceed. Still, only a few dozen beds are available at the Mississippi State Hospital, with 16 for Hinds County, county sheriff’s office officials told the Jackson Free Press.

“We’ve got 133 people that we are waiting to get access to 16 beds,” late Sheriff Vance said in his office on July 9. With him were Undersheriff Alan White, Assistant Warden Travis Crain and Chief Deputy Eric T. Wall. White said the number used to be 120. An evaluation can last between three months and one year, the assistant warden indicated.

“We have about 10 court-ordered detainees that have been ordered to (go to) state hospital that we still have to house because they don’t have a bed available for them,” White said.

“And they must have that evaluation before they can progress through the criminal-justice system,” the late sheriff added. “Because of the situation with the severely mentally ill people, they are basically stuck in our system.”

De Gruy indicated that the number 133 might not be just those awaiting an initial mental evaluation. “I’d be shocked if they’ve got 133 that are just waiting on an evaluation,” De Gruy said.

“They’re not all going to need a bed. And I suspect that there may be some other delays in those cases, like (waiting) on somebody to gather medical records to give to the (medical) provider, or (it) could be some other kind of a delay in getting everything to the (medical) provider.”

Jails: ‘Mental Health Institutions’

Before becoming a judge, Tomie Green worked as the Mississippi Department of Mental Health Services coordinator from 1980 to 1981. She said officials need to address the issue of pre-trial inmates needing mental-health evaluations to help speed up trials.

“Our state hospital has only (about) 50 beds to make evaluations for 82 counties and 22 circuit districts, only (about) 50 beds and only two security people to help take care of the 50 people while they are being evaluated,” she said. “So it takes years to get into the State hospital. So we’ve got no beds or not enough people to (perform the evaluation).”

Green said the procedure is that if an individual is not competent to stand trial, the court will remand them to the Mississippi State Hospital for restoration to competency. If, after a year, they are not brought back to competency, the next step is a civil commitment through Hinds County Chancery Court.

But the story does not end there. After an order for civil commitment, “two years later they are still in the beds at the jail because they can’t get a bed at the state hospital; there’s just no bed there to house them,” Green said.

“What I’ve got to do is pull from budget items where I’ve got some money from each judge to pay for (private forensic psychiatrist). By the time the private report comes back, if we commit them, the state hospital still has no room for them, and they just linger in the jail,” Judge Green added. “So when you see someone with five or six years (as a jail inmate), they may be there because that’s the only place they have a bed.”

This, she said, may be the case for “40% to 50%” of the jail population.

“The state has not developed a system for people who have not been convicted of any crime, may be charged, but can’t be convicted of a crime, and are being treated in the jail. Jails have become our new mental institutions,” she added.

Mississippi Public Defender De Gruy argues that an assessment does not have to occur at the state hospital and that Hinds County may be unwilling to go through other routes because of the cost. “(The County) may not want to spend a few thousand dollars to have a private evaluation, but the time that the case is waiting, it’s costing them money just to have them sitting there waiting on a bed,” De Gruy told the Jackson Free Press.

In the Mississippi Rule of Criminal Procedure, citations of the Mississippi State Hospital as a place for mental evaluations are paired with the option for “other appropriate mental health facility.”

State Hospital Responds

The section of the Mississippi State Hospital that performs mental evaluations for pre-trial detainees is called MSH Forensic Services. In lieu of an interview, MSH said in a Thursday, July 15, emailed statement to the Jackson Free Press that “MSH Forensic Services provides outpatient and inpatient psychiatric evaluations for pre-trial defendants and post-conviction appellants referred by the circuit courts. It also provides extended evaluation and comprehensive treatment for non-competent defendants and insanity acquittees.”

MSH avers that the wait time for an initial evaluation is 40 days beginning from the day that the hospital gets the order “and minimal background information.” The statement said that those in need of inpatient beds at the hospital wait longer.

“We are currently conducting some evaluations by telehealth, and some evaluations are being conducted by independent contractors, so not all evaluations are done here at the hospital,” the statement continues. “MSH Forensic Services has in recent years significantly reduced wait times for services including initial competency evaluations and inpatient evaluations and competency restoration.”

MSH says the number of individuals awaiting evaluations fell from 140 in 2016 to 88 in December 2020. The “bed capacity for Forensic Services was increased from 35 beds in 2016 to 56 in 2019, and a project has been approved that will create additional beds,” the statement promised.

‘Crippling’ Examiner Backlog

In July, DA Owens said the State of Mississippi has not come up with a solution for the backlog of evidence that the State Crime Lab needs to process before trials can occur. The delay is “crippling,” he said, with 150 outstanding autopsies. He cited the cost of recruiting forensic pathologists to Mississippi as a reason.

“The state crime lab analyzes evidence, including bodies and blood and semen and all types of things, to determine the cause of death and who did what,” Owens said. “We have to figure out a way for the major crimes, the murders, the rapes to be resolved. And right now, we have a significant backlog at the state medical examiner’s office.”

“That’s a significant issue that we really can’t resolve without the state looking into the backlog and making sure that they increase their capacity to give autopsy reports back, because that’s generally how you are able to prosecute the violent crime, by having the information you need to take something to trial and move on from there,” the Hinds DA added.

In January, Owens outlined how the problem at the State Crime Lab has increased in the last few years.

“Before last year (2020), we had 88 autopsies that were outstanding before the Mississippi State Crime Lab,” he told reporters. “And, you know, we had 137 murders in our county last year.”

Mayor Chokwe A. Lumumba discussed the problems at the State Crime Lab at the July 20 Jackson City Council Meeting after Jackson Police Department Chief James Davis talked about the lab’s slow pace of producing results. The mayor said he recently discussed the problem with Mississippi State Department of Public Safety Commissioner Sean Tindell.

“They haven’t opined what the plan is moving forward,” the mayor said and explained that the difficulty is not just about being short-staffed, but the staff also have to move across the state to testify at different courts.

“So they’re often having to leave the process of doing an autopsy to go and testify in court based on what their findings were,” Lumumba added. “The only solution I would imagine is getting more physicians that can do the evaluations.”

Ward 3 Councilman Kenneth Stokes said constituents have to delay burial plans because the bodies stay at the crime lab for many months. “Lots of people have been trying to have funerals cannot have funerals because of the state (crime lab) situation,” he said.

State Public Defender De Gruy said that the problem at the State Crime Lab is felt statewide and suggested ways to expedite the process by performing depositions with the medical examiner in the office.

“There are people who say, well, that that’s not necessarily going to move it forward because then they’re going to still want to call the person if the case goes to trial,” De Gruy said.

“But the truth is most cases don’t go to trial; most cases end in a plea.” The idea with doing depositions is to advance the case to get a deal sooner, he noted.

“There may be some other things that the Department of Public Safety and the medical examiner’s office can do to get the evidence back to the lawyers faster so they can move these cases faster,” De Gruy added. “That seems to be a problem we’re seeing across the state (where a) case can’t go anywhere because it’s a homicide case. They have to prove (the) cause and manner of death, and they don’t have a medical examiner’s report.”

De Gruy said it is a mystery to him why the state medical examiner’s office does not quickly create reports to speed up the persecution process. “I don’t understand exactly why the medical examiner is so far behind on producing reports in the first place. I don’t know if they don’t have enough doctors or why they don’t have enough doctors,” he said.

The 2021 House Bill 974 that Gov. Tate Reeves signed in March targeted the operations of the state medical examiner’s office, apparently to remedy the problems of getting speedy reports. It established the position of medical examiner investigators, who will be nonphysicians appointed and trained by the chief medical examiner and who “assist with the certification of deaths affecting the public interest.” They are authorized to assist with performing and completing autopsies.

Hinds County Deputy Public Defender Chris Routh said in an interview that his department has started seeing autopsies quicker since Dr. Mark LeVaughn left as the state medical examiner in January 2021. “We still do not have reports from some of the autopsies he performed,” Routh stated. “We are seeing reports much faster since he left.”

“For a long time there, we just weren’t getting autopsies for months or two or three years sometimes,” he added.

Quicker Evidence, Faster Trials

Judge Green said that the process of getting evidence ready delays the adjudication of cases. “What takes a long time is getting all the evidence to exchange it with the defendant, to get an autopsy, if necessary, to get witnesses, statements, and the more serious the trial is, the longer it takes,” Green said in the Zoom interview.

The deputy public defender, Routh, said there is a problem with speedily getting evidence to the defense from the district attorney’s office.

“I think that, frankly, if the district attorney’s office indicts a case, they need to have all of the evidence ready to go and ready to send to the person’s defense lawyer so that we can provide them a speedy and effective defense,” he said.

“If the State can’t get their case together and go to trial within a reasonable time, it’s not fair for someone to have to sit in jail for years while that happens,” he added. “We’ve got a lot of extreme problems, just getting basic, what we refer to as discovery, just like the basic evidence that the State says they have against people. They (district attorney’s office) almost never give that to us when they’re supposed to.”

The senior circuit judge said that many times there’s not a good evaluation to determine whether a case should not be a felony but a misdemeanor, and therefore never indicted. “And sometimes it just takes longer; like right now we are about two years behind in autopsies,” Green said. “If there is a death, we’ve got a problem of there not being available examiners.”

She said that the judicial process starts with law enforcement officials, who make arrests and charge offenses and then need to send cases to the DA.

“Sometimes I’ll have people in jail, and the DA doesn’t even know they are there because the municipalities have not sent the cases to them,” the senior judge said. “And when I sent them a show-cause (letter for them to state) why this person is down there, it’s 120 days, and they say that sometimes it is the first time they’re seeing (the case). We have a couple of cities that won’t send them to the DA, and they should be transferred over.”

Green did not name those cities but said via email on Aug. 27 that “we hope that municipal or city clerks will begin to forward the paperwork to the Circuit Clerk.” She also mentioned the need for a timely transfer of “Initial Appearance Orders and Preliminary Hearing orders to the District Attorney and the County’s Circuit Clerk, Zack Wallace.”

The senior judge said better case screening at the level of the police and even the district attorney before charging and indicting is vital, and she pushed back against the practice of “over arrest” or “overcharge” to “make the public feel good.”

“We should have the evidence, and if you’ve got the evidence, it shouldn’t be a problem,” Green said. “But we’ve a lot of problems with evidence—whether it is sufficient to convict someone.”

She said the prosecution should not wait until the case gets to the judges for screening, and then arrest based on a crime they have committed, not just to keep people in jail and off the streets.

“Let me give you an example,” she said. “You’ll have three teenagers and they are all caught in the car, the police officer pulls them over, they get (a radio information) that a murder has been committed and they described three black males in one car.” The police charges the three with murder and indicted.

“And sometimes it’s two years into discovery, and we realize we have only one shooter and he went back and picked up these two guys, and they ended up in the car with him,” she added. “If there’s an assessment by a DA of the cases before it gets to a grand jury, they may find out that two of the cases should have been misdemeanors, but again, our jail starts filling up because we keep indicting individuals.”

Green criticized over-indicting. “It may be a manslaughter or a self-defense, (but) we are going to get (the suspect) indicted for murder, so we can plead it down, we can offer a better plea deal when we knew in the beginning that that’s all it was—manslaughter or self-defense," she said. “But for the defendant that gets caught up in that, he’s sitting in jail if the bond is high, and he can’t move forward.”

Paying Public Defenders More

The senior judge said that assistant county public defenders should be paid better to guard against high staff turnover, which sets back defendants’ cases as a new defense attorney has to start again. She indicated that Hinds County has a full staff of public defenders, but they do not get the same salary as assistant district attorneys. The state government funds the district attorney’s office while the counties fund the public defendant’s office.

“And every time a lawyer leaves, the new lawyer coming in has to start the whole case all over again, and that backs up the docket,” Green added.

The Mississippi constitution provides that assistant DAs get $15,000 per year and up to 90% of the salary of the DA ($125,900), based on experience. It says that the county board of supervisors sets the public defender’s salary, which should not be less than the district attorney’s. It says nothing about assistant public defenders’ salaries, however.

“We need to have more public defenders that are paid comparably with the DA,” Green said. “If someone leaves the public defender’s office and goes right across to the DA’s office, they get an increase. So I do not really understand why they couldn’t have been paid well to represent the defendants charged with a crime.”

Deputy Public Defender Routh said that when the county employed him six years ago, his salary was $40,000 lower than a colleague employed at the same time at the district attorney’s office, even though he had a year more than her experience.

“There is and has been for a long time, if not always, a great disparity in the salaries,” he said in the phone interview. “It’s not just Hinds County, it’s a systemic problem, certainly in all of Mississippi, if not the country, where the services of public defenders are not valued the same as equally qualified district attorneys.”

“It keeps us from both getting and keeping really qualified folks to come work for us,” Routh added.

“It’s never a good situation where someone has to have a new lawyer every few months or whatever because those lawyers can’t afford to stay working at the public defender’s office.”

The public defender argued that because the U.S. Constitution requires people to have a defense counsel for crimes and there is no such requirement for district attorneys, they deserve better.

“So why are we paying the people who are doing the job that’s mandated by the Constitution less than we are the prosecutor?” he asked.

“We can’t keep folks other than folks who are either independently wealthy or dedicated to representing people to the point where sometimes it makes us poor,” he added. “It’s just kind of fundamentally unfair, and there’s no reason for it.”

Right to A Speedy Trial

State Public Defender De Gruy said there are various reasons why cases delay getting to trial, but added that taking up to one year maximum may be a sufficient goal at this point.

“The Mississippi Supreme Court has said a person should be brought to trial in eight months,” he said in the phone interview. “And then we have a 270-day rule, which starts with arraignment, which is not until after indictment.”

Owens said in May to the Jackson City Council that Hinds County is not having speedy trials. “And we know best practices is that from arrest to conviction has to be a year. Here in Hinds County, we’re close to about two and a half to three years. That means we’re not solving crimes fast enough,” the DA said.

“I need help. I have more than 3,000 cases in my office. I have 12 (attorneys handling) 3,000 cases.” The Legislature funded two assistant district attorney positions for one year in the last legislative session (2020-2021) as a partial remedy to the situation.

While diverting hundreds from jail and their cases being dropped in exchange for a commitment to different diversion programs can help, another practice leads to an increase in inmates, Owens explained to the city council.

“Now, in (our) administration, if someone commits a crime (when) they’re out on bond, and that crime is punishable by more than five years and a day, we immediately move to revoke their bond,” he said. “Then they won’t be eligible for a bond until the case is resolved. But that’s the whole balloon effect, which would put too many people in the sheriff’s jail.”

De Gruy told the Jackson Free Press that getting homicide cases resolved is indeed getting increasingly difficult because of delays at the State Crime Lab. He, however, noted that the City of Jackson, which District Attorney Owens said is responsible for 85% of the crime prosecuted in Hinds County, has its own crime lab.

However, Jackson Police Department spokesman Sam Brown said in a phone interview that “80% to 90%” of the evidence collected goes to the State Crime Lab.

“We have a mobile crime lab that goes out and gathers the evidence and processes them; any test that needs to be done, they will go over to the state,” he said.

“Depending on what the situation is, that could be anything from a second opinion or a more definitive answer or analysis, something like that so that they would send it over to the state,” Brown added.

“A lot of the crimes that are committed, like homicide and things like that, or a lot of the drug tests, we would send that information to the State Crime Lab for transparency,” Brown added.

Owens argued for more support for his office by the City of Jackson in the July interview. “The police departments are functioning at all-time lows and have more crime. And we know that we know there’s a police shortage as such the quality of what we can get from those departments has diminished just sheerly because of capacity,” the district attorney said.

“They got some great people over there working really hard, and we appreciate the brave jobs they do, but we need more support to be able to prosecute cases more fully. A few hundred thousand dollars would go a long way in helping us solve and prosecute the crimes that are happening in Jackson.”

Stuck in the System

Late Sheriff Lee Vance said a detainee should not have to be in detention for more than one year. “Some of the resources that are needed are not in line with how many people are somewhat stuck in the system pre-trial,” he told the Jackson Free Press weeks before he died. “That’s definitely a big problem because that leads to people being housed in our facility for a lot longer than they should be.”

“Our responsibility is to house individuals really indefinitely under the set of circumstances that we’re dealing with now,” the late sheriff added. “In a perfect system or at least an improved system, you could probably predict somebody may be down there (at the detention center) a year or so before they go to trial. But, circumstances get in the way of that, and so we end up being the place where these folks pretty much get stuck.”

Based on documentation Undersheriff Alan White provided to the Jackson Free Press, 301 people in Hinds County Detention Centers on July 2 have spent up to six months there. Ninety seven have spent between six months and one year, 65 between one and two years, 29 between two and three years, 15 between three and four years, and 14 people have spent over four years behind bars.

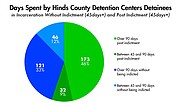

One hundred and seventy-three inmates have spent more than 90 days in jail post-indictment, 32 between 45 and 90 days post-indictment, 121 have spent over 90 days without being indicted, and 46 have spent between 45 and 90 days in detention without being indicted.

One of the Hinds County detainees, whom Sheriff Vance did not name, has been in the Hinds County Detention Center for eight years and has been to the Mississippi State Hospital several times. Health officials have not declared him competent to stand trial. “So until he could stand trial, we are kind of stuck with him,” Assistant Warden Crain said.

Bond Denial, A Problem

Routh disputes that mental-health evaluation needs swell up the jail, contending that the court slaps a high or no bail on defendants for no good reason.

“The problems that the jail itself is having are all compounded, if not made by the lengths of pretrial detention,” he said. “It’s the refusal to give bond in a lot of these cases where warranted.”

“And it has gotten better with the state hospital about getting those mental evaluations done in a timely manner.”

Routh said the lag in discovery and lack of autopsy report and bond denial bogged down Justin Mosley’s case and prolonged his stay in detention. “Mr. Mosley sat in a lengthy pretrial detention,” he said. “He was denied bond at least once.”

The law provides that everyone accused of a crime is entitled to bond, and Routh protested the rationale for denying Mosley a bond.

“The real key issue to me is that he wasn’t given bond. And everyone likes to get all up in arms and complain about people being dangerous to the community. But the fact of the matter is everyone charged with a crime is entitled to bond; they’re entitled to pretrial release,” he said.

“Pretrial detention should be the exception, not the rule, and we asked the court to give (Mosley) a bond which he’s constitutionally entitled to, and then they denied it,” Routh added.

“When his next attorney, Mr. Harrison, made the same request for a bond, Mr. Mosley took his life before the court even ruled on the bond issue.”

“But you know,” Routh said, “if Mr. Mosley had been out on bond, this (hanging in a detention cell) wouldn’t have been an issue for him.”

Email story tips to city/county reporter Kayode Crown at [email protected]. Follow Kayode on Twitter for breaking news at @kayodecrown.

More stories by this author

- City Council Votes on 2022 Legislative Agenda, Wants Land Bank, Water-Sewer Debt Forgiveness Extension

- Who Is the Hinds County Board of Supervisors’ President?

- JPS Starts In-Person Learning Tomorrow, Enhanced COVID-19 Protocol

- City Engineer: Despite Improvements, Severe Winter Storm Could Wreak Havoc

- Mississippi Supreme Court Appoints Senior Status Judge, Justice to Hinds County Cases

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

comments powered by Disqus