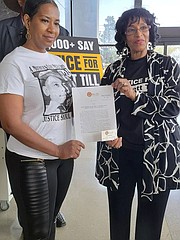

A collection of Emmett Till’s living family members, activists, and supporters spoke at the Mississippi Capitol and marched on the Sillers Building on March 11, 2022, demanding justice for Emmett Till and the prosecution of Carolyn Bryant-Donham. Photo by Nick Judin

Emmett Till disappeared into Bryant Grocery and Meat Market to buy candy on an August evening in 1955. Wheeler Parker, his cousin, went with him into the Money, Miss., store. Parker stepped back out shortly thereafter, and for one minute, the 14-year-old visitor from Chicago was alone in the store with Carolyn Bryant, the 22-year-old clerk of the store her husband, Roy, owned.

Just one minute later, Till’s cousin from Mississippi stepped in. Simeon Wright watched Till pay, and they left together.

Few lost moments in history have been put to such scrutiny. Two witnesses to those obscured seconds emerged from the grocery that day, but only one would ever be afforded the right to testify about them. Carolyn Bryant told her story in the Tallahatchie County Courthouse in Sumner that September with her husband and his half-brother on trial.

Emmett Till, Bryant claimed, grabbed at her hand when paying, then rounded the counter and grasped her by the hips, his arms around her back. What she says he told her next—the sexual euphemism about white women she declined to speak out loud—would be the death of Emmett Till, however much a lie and no excuse for murder in any case. After all, in the words of murderer J.W. Milam, he was “that boy that done the talking down at Money.”

Somehow, less interrogated by the public, is another moment in the same trial briefly after Bryant’s story. It is contained in the testimony of Till’s uncle, Mose Wright, who at the trial stood and pointed down at J.W. Milam and Roy Bryant, knowing what that could mean for his life and safety.

It was the early hours of the 28th of August when Milam and Bryant descended on the Wright household, armed and looking for Till. Before Milam and Bryant and their other accomplices took Till away, they stopped by the car, Mose Wright said, and asked someone in the vehicle if the boy they had was him—the one from the grocery.

“Yes,” responded a voice in the car, a “lighter voice than a man’s,” Wright testified.

The voice, logic argues, could be no one other than Carolyn Bryant. For all of the endless details, precise timelines, for all the deceptions and lies in that courtroom or the just-so story told to Look Magazine after the acquittal; for whatever Till said in the store, for his whistle or the way his hands might have brushed against Bryant’s when he paid for his candy, Mose Wright’s testimony points one more unavoidable finger—what he swore in that courtroom is that Carolyn Bryant helped lynch Emmett Till.

The Last Living Accomplice

Almost 67 years later, Deborah Watts, co-founder of the Emmett Till Legacy Foundation, stood beneath the Mississippi Capitol dome, and the topic on her lips was determination to see long-deferred justice for her then-14-year-old cousin killed that night in Leslie Milam’s barn.

“We’ve got a promise to many that we would persist, and that’s why we’re here today,” Watts proclaimed on March 11, 2022.

The family of Emmett Till is once again calling for justice, nearly 70 years past young Till’s vicious murder, tied to a cotton-gin fan in the Tallahatchie River. Gathering at the steps of the Mississippi State Capitol’s rotunda on March 11, speakers from Emmett Till Legacy Foundation called for charges against Carolyn Bryant, now Carolyn Bryant Donham, who later divorced Roy Bryant and remarried. She is the last known living instigator of Till’s murder.

“Mamie Till-Mobley … left this earth not knowing if there would ever be justice for (Till’s) brutal murder, but she also left open his casket so we would bear witness to the hate that has been embedded in our DNA since the slave ships arrived in America,” Watts said about the boy’s mother. A photograph of Till’s mangled face in his casket appeared on the cover of Jet Magazine on Sept. 15, 1955.

“The murder remains unsolved,” she continued. “And the last living accomplice in that murder case is Carolyn Bryant.”

‘The Culpability of Carolyn Bryant Donham’

Of the many distortions that followed Till’s lynching—including the early lie that Bryant and Milam had simply let Till go—the momentary encounter between Donham and Till is the most scrutinized, in no small part because she is still alive, reportedly living in Durham, N.C. Donham’s testimony in 1955 to an all-white jury in Sumner has never lined up with other witness testimony of the event, including Till’s family and friends who saw no such action.

An all-white jury acquitted Bryant and Milam, after which they admitted to the crime in a paid interview with Look Magazine with a white journalist who hid facts. Although that interview firmly established the men’s guilt, it also concealed the participation of other men who were never named, charged or tried with the lynching.

At Friday’s event in the Capitol, Jaribu Hill, executive director of the Mississippi Workers’ Center for Human Rights, said Donham’s participation was a key part of the lynching of Till. “As my sister Deborah said earlier—exposing the lynching—it wasn’t a killing, it wasn’t a murder. It was a lynching. … We want full acknowledgement of the culpability of Carolyn Bryant Donham.”

“Remember,” Hill continued, “it’s Carolyn Bryant, the 21-year-old white woman who fingered a child, knowing that she was pointing him out to his murderous, killer husband. … We want justice. We want the original warrant that should have been served on her in 1955.”

From Lip Service to Justice

For Joshua Harris-Till, another cousin of Emmett Till, justice has for too long been lip service, mourning without action on the part of the powerful. “To ask my family to think about forgiveness is to ask us to forget about justice. When will we get the justice that we are due? When will she be held accountable for her actions? When will she have to actually face the ramifications for what happened in that store?” he said of Donham.

Several attempts to bring Donham to trial have already failed—first in 2007, when a Leflore County Grand Jury declined to bring manslaughter charges against Donham, declaring a lack of sufficient evidence. Late last year, the U.S. Justice Department closed yet another investigation into Till’s lynching without further charges against Donham for perjury or any other crime.

Renewed interest in Donham’s involvement followed her 2008 interview with historian Timothy B. Tyson for his book “The Blood of Emmett Till.” Over the course of two recorded interviews with Donham, Tyson wrote in his book that she had firmly acknowledged that her testimony at the trial had been a lie.

But Tyson has acknowledged that her confession had not been recorded. The historian said that the incriminating statement had been made just prior to the recording. “Carolyn started spilling the beans before I got the recorder going,” Tyson said at the time. “I documented her words carefully.”

Without an ironclad admission that Donham had lied, the U.S. Justice Department closed the case in late 2021.

‘It Empowered All Of Us’

At the rotunda steps, activists and extended family members of Till presented their case to the public and then walked across High Street to deliver their letter to the office of Attorney General Lynn Fitch, along with 250,000 signatures on a flash drive calling for justice on behalf of Till and his family.

For many of those gathered in support of the march, the unpunished lynching of Emmett Till is representative of the unfulfilled promise of justice facing Black Americans today. Akil LaBertis, carrying a banner with the words “Justice For Emmett Till,” told the Mississippi Free Press that the void of responsibility for killers like Till’s remains today. “A lot of things like this are still happening (today). The game doesn’t change, just the players.”

The story of Emmett Till usually garners sympathy when it is told. But the activists, the family members and the speakers present at the event wanted more than words of support—they want action, material consequences for whatever participants are still alive.

“There’s a value gap,” LaBertis said. “Everyone says they know the importance of (justice), but they don’t know the value of it, the cost of it.”

Reena Evers-Everette—who is an advisory board member for the Mississippi Free Press—is the daughter of civil rights icon Medgar Evers, whom white supremacist Byron De La Beckwith murdered in Jackson in 1963. She is familiar with a long and winding road to justice.

“The Medgar Evers family knows that pain,” she said at the rally. “Knows the sight of blood.”

They know resilience, too. “The strength and courage that Mamie Till displayed continuously, even before her son stepped foot on that train from Chicago, and then when the casket came on the train back to Chicago, her strength and courage went viral, as we say now, but it empowered all of us,” Evers-Everette added.

Time Running Out

Time for the justice the speakers demand is running out. Keith Beauchamp, the documentarian whose film “The Untold Story of Emmett Till” led to the original 2004 re-opening of the case, expressed the difficulty of fruitlessly seeking real accountability. “It is frustrating to come back every decade or so and stress the importance of seeking justice for Emmett Till,” he said. “… I have to keep screaming and hollering about the importance of getting closure. Not only for the family of Emmett Till but for this whole nation.”

Beauchamp, also an MFP advisory board member, is a writer and producer of the new feature film “Till” based on his long-time work on the case.

Mose Wright passed long ago, in 1977. Mamie Till-Mobley died in 2003. Simeon Wright, one of Emmett’s cousins present both at Bryant’s Grocery the day of the encounter and later, at Till’s abduction, died in 2017.

Murderers J.W. Milam died in 1980 and Roy Bryant in 1994.

A representative from the Public Integrity division of the Attorney General’s office accepted the letter to Fitch who has not responded about the future of the case. The Office of Attorney General Lynn Fitch did not return a request for a comment to the Mississippi Free Press.

This story originally appeared in the Mississippi Free Press. The Mississippi Free Press is a statewide nonprofit news outlet that provides most of its stories free to other media outlets to republish. Write [email protected] for information.

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

comments powered by Disqus